Eddie Paddock talks about the virtual reality at NASA Monday, Feb. 26, 2018, in Houston.

Eddie Paddock talks about the virtual reality at NASA Monday, Feb. 26, 2018, in Houston.

Photo: Steve Gonzales, Houston ChronicleEddie Paddock uses virtual reality equipment in the 'pit' at NASA Monday, Feb. 26, 2018, in Houston.

Eddie Paddock uses virtual reality equipment in the 'pit' at NASA Monday, Feb. 26, 2018, in Houston.

Photo: Steve Gonzales, Houston ChronicleEddie Paddock talks about the virtual reality at NASA Monday, Feb. 26, 2018, in Houston.

Eddie Paddock talks about the virtual reality at NASA Monday, Feb. 26, 2018, in Houston.

Photo: Steve Gonzales, Houston ChronicleEddie Paddock (left) watches Houston Chronicle Reporter Dwight Silverman use virtual reality gear at NASA Monday, Feb. 26, 2018, in Houston.

Eddie Paddock (left) watches Houston Chronicle Reporter Dwight Silverman use virtual reality gear at NASA Monday, Feb. 26, 2018, in Houston.

Photo: Steve Gonzales, Houston ChronicleStanding on the end of the robotic arm outside the International Space Station, the Earth appears as a vast, azure expanse 250 miles below. Staring down, it feels as though you could easily, maybe even happily, fall into that glow. It’s intoxicating.

But look up, and the total blackness of space — dotted by stars and planets bright enough to overcome the reflected glare of sunlight off the space station — is even more overwhelming. Out here there is majesty above and below, and in the strata between is the technological marvel of the station itself, prickly with antennae, solar panels, puffy insulation, wiring and a docked Soyuz spacecraft, which is ultimately your ride back home.

The sight is beautiful, awe-inspiring, humbling and a hundred other joyful adjectives, none of which do the scene justice.

Too bad it’s not real.

Remove the virtual reality headset, and you’re back on Earth. Specifically, you’re in a small office in Building B9 on NASA's Johnson Space Center campus, surrounded by high-tech hardware — sensors, cameras, large display monitors — and the mundane furnishings of government life: aging desks, beige walls, plywood dividers, fluorescent lighting. It’s a jarring comedown after frolicking in simulated orbit.

From the archives: NASA was on the cutting edge with virtual reality in 1992

But this is one of many rooms at NASA where astronauts come to train for flights to the International Space Station and, maybe in the near future, to the moon and Mars. Here, NASA’s modern knights go over processes they’ll employ in spacewalks and ISS procedures. Some of what they learn here may save their lives.

For almost 30 years, NASA has been building a virtual reality universe behind these 1960s-era walls at Johnson Space Center, cobbling makeshift headsets and writing homegrown software to train astronauts for life in space long before they suit up. Those early efforts were crude and expensive, but kept the space agency on the cutting edge of virtual reality even as the technology seemed to vanish for a while for consumers.

$40K headset now $500

The technology is now enjoying a renaissance, and NASA is rushing to take advantage of it. VR headsets that gamers purchase for a few hundred bucks and connect to off-the-shelf personal computers are supplanting those that used to cost NASA tens of thousands of dollars to design and build.

And NASA’s VR software, which allows the stunning recreation of the ISS, the Earth below it and cosmos above, is slowly being nudged out by commercial and open-source 3D software that’s also used to build popular video games. Besides the cost savings, NASA can take advantage of advances in VR technology almost as fast as it comes to market.

“You can leverage all the work the commercial world is doing, instead of paying an expensive engineer to maintain complex software,” said Eddie Paddock, the manager of the VR effort at Johnson Space Center. The four employees and two interns who work with him are responsible for creating simulations and training astronauts with them.

Paddock’s lab is dotted with artifacts from VR’s earlier epoch. There are headsets that look like steampunk props from a Terry Gilliam movie, but they’re very real — NASA engineers built them by hand back in the day, at a cost of $30,000 to $40,000 each. Now, you can bring home from Fry’s or MicroCenter a consumer headset with dramatically better resolution and faster displays for less than $500.

The space agency’s interest in virtual reality dates to the early 1990s, though some old-timers say NASA was exploring the concept even before the term “virtual reality” was coined in the mid-1980s.

Photo: Steve Gonzales, Houston Chronicle

Eddie Paddock demonstrates Charlotte, which astronauts use as part of virtual reality at NASA Monday, Feb. 26, 2018, in Houston. Astronauts wear VR headsets and software turns Charlotte, a metal frame in the shape of a cube, into a piece of equipment to be installed on the outside the International Space Station.

The VR lab, founded in the early 1990s by David Homan, was involved in training astronauts during the Space Shuttle era. Homan made his earliest mark by using VR to train the astronauts who were involved in the spacewalk to repair the Hubble Space Telescope.

One of the contraptions built for that mission is still used in the lab: Charlotte, a metal cube with handles on it that’s attached to a web of cables. It simulates the feel of an object that has no weight, due to the lack of gravity in space, but still has substantial mass. Astronauts who spacewalk to do work outside the space station spend time wearing VR headsets, pushing and pulling on Charlotte’s handholds, and in their VR headsets they might see a satellite or other mission hardware instead of a spartan metal cube — just as their predecessors did 25 years ago.

Paddock says astronauts who go through the training report back after they return home that they felt “as though they had already been there” thanks to this training. They can practice difficult and even risky procedures in the comfort of an air-conditioned office.

“Space is a dangerous place,” Paddock says. “The lab is an environment that is much less hazardous.”

Problem to solve: Research shows lungs heal more slowly in space

Before its time

Virtual reality first hit public consciousness in the mid-1980s. Jaron Lanier, considered the father of VR, founded VPL Research in California in 1984 with a goal of bringing virtual reality to the masses.

VPL’s equipment looked remarkably like modern VR gear today. A headset with a pair of video displays fits on the user’s head. Headphones are placed over or in the ears. Both the sights and sounds of the real world are replaced by images and audio generated by a high-powered computer.

The system tracks head, hand and sometimes full-body movement in a variety of ways, giving the user the feeling of moving through and interacting with the virtual world.

In its earliest days, virtual reality was more frustrating than fascinating. The computers of the time struggled to keep up with human movement, creating a lag in the visuals that could produce motion sickness. And the visuals were primitive, looking more like crude cartoons than anything resembling reality, virtual or otherwise.

Photo: Steve Gonzales, Houston Chronicle

Eddie Paddock uses virtual reality equipment in the 'pit' at NASA Monday, Feb. 26, 2018, in Houston.

It was also expensive. The earliest VR rigs cost hundreds of thousands of dollars. By 1992, though, a Houston company called Spectrum Dynamics was selling virtual reality systems to home and business users for $25,000, according to a Chronicle story from that year.

But the initial VR wave crested and died for consumers, who couldn’t justify the cost and were turned off by the quality of virtual worlds. However, that wasn’t the case at NASA, which continued to explore it for both training and evaluation of design.

“NASA has always been on the cutting edge of virtual reality,” said Zvi Greenstein, general manager for consumer virtual reality at Santa Clara, Calif.-based Nvidia, which makes hardware and software NASA uses in its VR lab.

Not just off-the-shelf

While a lot of the VR training happens on the ground, some of it needs to take place in space. Because astronauts spend months on the space station, Paddock says, their training needs to be refreshed periodically. Or, if a spacewalk is required to fix something outside the station, he and his team can put together a VR training routine and upload it to the ISS.

Exploration: NASA wants your help in search for new planet beyond Pluto

Right now, the VR gear used on the space station is a hack in the old-school NASA VR tradition. The headset used by the ISS crew is a full-sized Lenovo ThinkPad laptop mounted onto a headpiece with the screen fixed in front of the wearer’s face. What would be clumsy and awkward on Earth is not a burden in the microgravity of orbit. But still, it’s not the best setup, Paddock says.

Photo: Photo Courtesy Of NASA

NASA astronaut Robert S. Kimbrough uses a virtual reality headset cobbled together from a laptop computer and a custom face mount aboard the ISS in December 2016. This setup is being replaced by newer VR headsets made by Oculus, which is similar to those used by gamers.

So, in April, a SpaceX supply mission will bring the ISS’ residents some newer gear: Two VR headsets made by Oculus, the company credited with rebooting public interest in virtual reality, and a pair of faster HP ZBook laptops to power them.

The headset, a model called the Oculus Rift, sells for $399. The ZBook has a price tag on HP’s website of around $2,000.

The newer equipment costs “a lot less than the $30,000 to $40,000 we used to spend building these things in the ‘90s,” Paddock says.

Still, off-the-shelf doesn’t always cut it in the unique demands of space. For example, the Oculus headset’s motion-tracking system uses a feature similar to the accelerometer in a smartphone that counts your steps or knows when you’re traveling in a car. However, that technology requires gravity to work, and . To get around that, the VR team has affixed an ordinary Logitech webcam to the front of the headset, which gives the system visual cues about movement instead. The ZBook, while powerful, doesn’t quite have the muscle needed to create a realistic environment, so software tweaks had to be written.

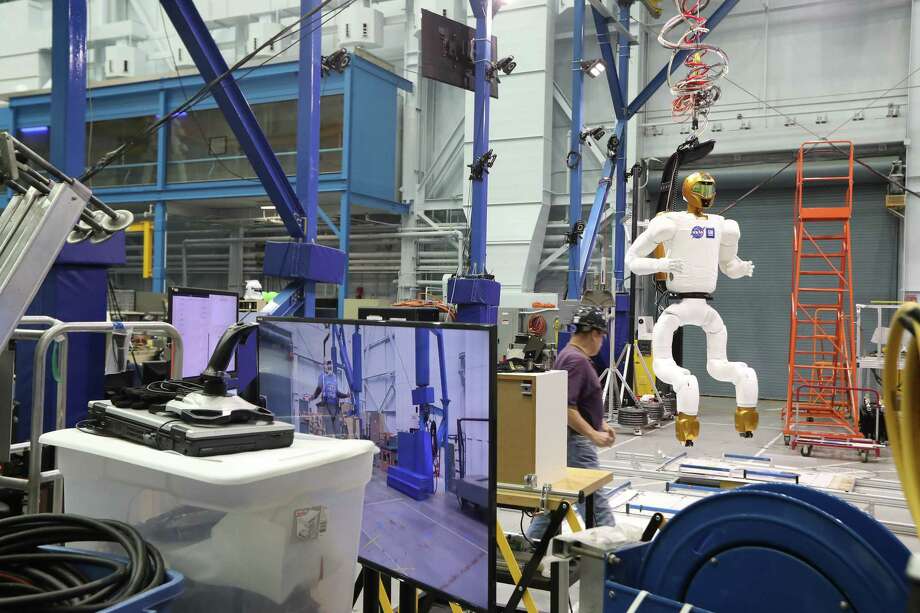

Photo: Steve Gonzales, Houston Chronicle / Houston Chronicle

A robot being used with virtual reality equipment at NASA Monday, Feb. 26, 2018, in Houston. ( Steve Gonzales / Houston Chronicle )

Paddock says the overall cost of the newer rigs are about half that of the “laptop on the head” design. And he says his team is looking forward to future headsets that will incorporate cameras built into the headsets, which will make it much easier to develop the software to translate motion in the VR world.

Translator

To read this article in one of Houston's most-spoken languages, click on the button below.

One of the uses for the onboard VR system: Refreshing crew members on use of SAFER, a jetpack built into the suits used in spacewalks. SAFER, or Simplified Aid for EVA Rescue, allows an astronaut to return to the shuttle should she or he become untethered and float away. It’s a safety feature that’s never had to be used, and hopefully never will be, but astronauts need to keep up their training on the feature. The ISS crew dons their VR gear and regularly simulates having to activate SAFER.

“It’s a lot easier, and a lot safer, to do it in VR than to have them suit up and do it in a spacewalk,” Paddock said.

Space doll: Mattel unveils Barbie inspired by NASA's 'hidden figure' Katherine Johnson

Two-way payoff

The software that has long been used to display the virtual worlds in NASA’s universe is called DOUG, which stands for Dynamic Onboard Ubiquitous Graphic. It both renders the spectacular images seen in NASA’s VR system, as well as handle the physical rules of how objects behave. It looks as good as any rendering engine found in commercial applications, such as computer games.

But it is expensive to update and maintain, and NASA is starting to turn to the same kind of graphics engines found in popular video games. The space agency is working with two in particular: the Unreal engine, developed by Epic Games, and Unity, an open-source engine that claims to be the most-used game renderer in the world.

In addition, NASA is using an Nvidia application called the Holodeck — named after the virtual reality playground in “Star Trek: The Next Generation” — to begin evaluating designs for the Deep Space Gateway, a space station that is planned to orbit the moon and ignite the agency’s manned exploration efforts in deep space.

In a room called the PIT (Prototype Immersive Technology) in another Johnson Space Center building, a user can don an off-the-shelf VR headset from Vive — which has a list price of $599 — and explore both the inside and outside of the Gateway. Nvidia’s Holodeck software lets multiple people explore a virtual environment at once, and even annotate what they see.

“It makes virtual reality a collaborative experience,” Nvidia’s Greenstein said.

NASA is awaiting designs from the companies who have won bids to provide modules for the Gateway, and will be able to drop those proposed designs into the Holodeck software to evaluate the process.

“Better that we find out about issues this way than when we’re actually building from the designs,” Paddock said.

In another location at Johnson, the Unreal engine is helping provide astronauts with a feel for different types of gravity. ARGOS, or Active Response Gravity Offload System, utilizes a harness system that can simulate the gravity of the moon or Mars, or the microgravity of orbit. It’s similar to NASA’s famed Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory, a giant swimming pool in which astronauts have trained for years to simulate weightlessness.

Commercial space: Falcon Heavy launch fortifies resolve of other commercial space projects

“This helps NASA move away from the challenge of having an astronaut submerged in water for training,” said Simon Jones, director of enterprise for Epic Games. “At the same time, they can recreate the International Space Station in virtual reality, so it’s much more realistic.”

NASA’s work with these technology companies pays off for them as well. They learn from NASA, and vice versa, Paddock said.

For example, during a recent visit to NASA, Oculus Chief Technical Officer John Carmack was interested in the tweaks Paddock’s team made so virtual reality software runs more smoothly on the HP ZBook laptop. Carmack was one of the co-founders of Dallas-based id Software, and wrote the graphics engines for the classic first-person shooters “Doom” and “Quake.” Those tweaks could potentially help the gear made by Oculus, which is now owned by Facebook, run on home computers that are less powerful, and thus less expensive.

Dwight Silverman is the technology editor for the Houston Chronicle and the grillmaster for the TechBurger tech news site. Follow him onTwitterandFacebook.

Get more tasty tech news atTechBurger. And follow us onTwitterandFacebook.

Subscribe to the Chroniclefor regular access to TechBurger stories and to be able to comment.

Read Again NASA's virtual reality journey uses same software, hardware as gamers : http://ift.tt/2p4yVioBagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "NASA's virtual reality journey uses same software hardware as gamers"

Post a Comment